Food in Judeo-Sephardic Songs

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

Cantares Con Savor - A Taste of Sephardic Songs

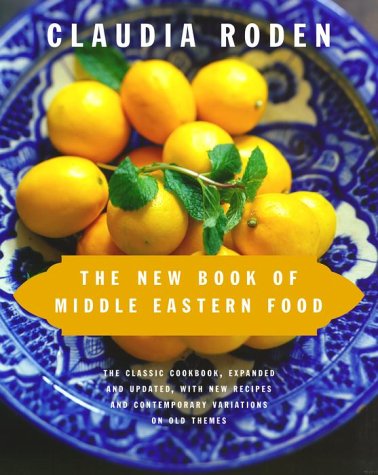

The Mediterranean cuisine - renowned for both the delicacies of its flavours and for its health benefits - is extolled by people around the world. Sephardic food, born in the Mediterranean, enhanced by the exigencies of Jewish tradition and nurtured lovingly by the Jewish housewife [ama de casa], is a special case which proves the rule - as you can see from the collage above. Many folksongs in the Ladino repertoire make specific mention of Sephardic food, both literally and metaphorically. You may find it interesting to compare these songs with ones sung in Yiddish about Ashkenazi food - I personally find the comparison fascinating.1

* * * * *

La mujer y la sartén en la cocina se llevan bien. [The woman and frying-pan in the kitchen get on well together.]

Let's begin with berendjena [eggplant, or aubergine] which, according to Claudia Roden, doyenne of Sephardic cooking, is the Sephardic Jews' most popular vegetable. Seven methods of preparing eggplants are collected in a song from Rhodes entitled Siete modos de guisar las berenjenas [Seven ways of cooking eggplants] - this is actually a truncated version of an early 18th century copla describing 35 different eggplant dishes!2 Jane Peppler, who sings in the video below, has noted down recipes alongside each of the stanzas of the song, and I've also collected a few articles on preparing aubergines which you may find useful.3 (Here is another version, sung by Mara Aranda, and here are the musical notes).

>

Actually, while this song - and especially the original copla - is basically about eggplant dishes, it also provides us with information about traditional Sephardic attitudes towards women.2 Another song entitled La berendjena is actually about a fruit vendor (discussed in the lecture on "Making a Living"). A third song featuring eggplants is El Dió la mate esta Grega [May God kill the Greek woman] 4 - the Great Fire of Saloniki is usually ascribed to desecration of the Shabbat (see La cantiga del fuego [The song of the fire]); in this song, blame is placed specifically on a woman: "May God kill the Greek woman who burned the eggplant; she burned down Thessaloniki and left us poor and charred."

Other Sephardic fare - burekas, pastelas, bimuelos, fritas, etc. - will be presented in the contexts of the songs below.

Festival dishes and customs

El que tiene hijas, comera biñuelos. [Whoever has daughters will eat doughnuts.]

Festival foods are most lavishly described in Purim and Hanukkah songs, and mentioned incidentally in the songs of other festivals. Flory Jagoda has recorded songs featuring festive foods about most holidays, either songs she remembers from her native Yugoslavia or ones she has composed herself. In Laz tiyas [The aunts], for example, she relates how each of her aunts would be responsible for hosting a different holiday, the whole family gathering together to eat and sing.

The co(m)plas de Purim, songs which recount the story of Purim and describe its customs and special dishes, tell us a lot about the festival. La celebración de Purim / Alabar quero al Dio [I wish to praise God] informs us that the tables were laden with baked, grilled and fried meat and fish, salads, fruit, almond cookies [maronchinos] and, especially, wine! Esta noche de Purim [This night of Purim]5 tells us about courtship customs: Shabbat "Zakhor", the sabbath preceding Purim, was also known as Saba de las noviecas [the sabbath of the brides].6 According to the song, bakers would be busy making all sorts of delicacies for the bride and groom, who would exchange gifts with each other. The bride would send trays of cofita [sweets], which were reciprocated by trays of new clothing for the young bride.7

Hanukkah foods8 and customs are described in the popular songs Dak il tas [Beat the plate], Quita'l tas [Bring out the plate], or Hazeremos la merenda [We're having a meal]. On the last day of Hanukkah, the Sephardim of Turkey would visit one another, each bringing along something for the merenda ["pot-luck" meal]. In Saloniki, charitable women would collect flour and oil to distribute to the poor, so that everyone would be able to feast on burmuelos / bimuelos, puffy fritters deep-fried in oil.9 As we hear in the song Merenda de Hanuká [A Hanukkah snack], children would go chanting and singing from house to house, asking for oil, flour and sugar. They would also sing Vayehi mikets [And it was at the end], a parody of the Biblical text read on the Shabbat of Hanukkah where Joseph interprets the dream of Pharaoh - the dream here is of burmuelos or piticas [little pitas]!

Bimuelos/Burmuelos and Pastelicos

Ocho kandelikas [Eight candles], a very popular song by Flory Jagoda, includes mention of pastelikos [little pastries] filled with almonds and honey.

In contrast to the Yiddish repertoire, there are hardly any songs in Ladino which mention food eaten on Shabbat.10 A song which does hint at the importance of preparing special food on Shabbat is Oy es viernes la mi madre [Oh, it's Friday, mother], in which the daughter worries about what to cook for the Shabbat visitor.

A Passover counting song from Sofia, Bulgaria, which may have been sung towards the end of the seder [Passover festive meal] is Ke komiash duenya? [What did you eat, Lady of the house?]11 Beginning with a pheasant on the first night, two roosters on the second and three flying doves on the third night, the lady's intake increases to twelve bottles of retsina on the twelfth night! This song is reminiscent of and may possibly be related to European cumulative songs, e.g., "There was an old lady who swallowed a fly" or "The twelve nights of Christmas".12

A Passover song from northern Africa goes: "Sister Simcha, Passover has arrived. It's time to put away any leavened food and keep only what is kosher for Passover." Much more memorable than this song is its bawdy contrafact, a song entitled Jacó y Mazaltó (or: Pescado frito [Fried fish]) featuring the same melody as the Passover song but with entirely different words. "Jacob is selling fried fish. Where did he fry it? In Mazaltov's frying pan. Oh, what a pan Mazaltov has! Who heated it up? Mr. Jacob." The ensuing verses talk about "hot bread" baked in Mazaltov's "oven", and "fresh parsley" planted in her "garden"!13 (This melody is also used for the Shabbat piyut Lekha Dodi [Come, my beloved]).

Food in the life cycle

Desdichada la cazza ande la gallina canta como el gallo. [Woe to the house where the hen sings like the rooster.]

The most significant event in the life of a Jewish couple was the birth of a son, as we hear in El parto feliz / Copla de parida / Cantica del parido / Ay, que mueve mezes [The happy birth / Song of the new mother / Song for the new father / Oh, nine months] - a copla sung on the night preceding the newborn's Brit Mila [circumcision]. In one of the versions of such birth songs, the first thing the new mother says after the birth is, "I haven't had anything to eat!" She is brought a roasted chicken; then her husband comes in, his arms laden with fish, coins (ducats) - apples and pears, in some versions of the song - and plenty of wine for himself and his comrades. In a truncated version popular with Bulgarian Jews - S'aqueja la parida [The new mother complains] - the mother polishes the chicken off and leaves the bones under her bed!

Food has a symbolic function in many of the songs related to the life cycle. Mention of the hen in many of the birth songs may quite possibly hearken back to ancient Spanish fertility rites.14 Food highlights the distinction between "desirable" and "undesirable" (e.g., the birth of a boy vs. a girl; mother vs.mother-in-law). As we see in two other circumcision songs, Levantáivos el parido [Awake, new father] and Parida está la parida [Mother, here's the mother], good food [los buenos vicios] is offered to the mothers of sons, but the mothers of daughters have to make do with sardines! Similarly, a betrothal song - Dáile a la suegra una sardina - describes the appropriate meal for the for the bride (a chicken) as against her mother-in-law (a sardine). Even age is discriminated against: according to the mikveh [ritual bath] song La novia se bañaba [The bride bathes], brides deserve soft bread, a bed of roses and a fine chicken, while old women deserve hard bread, a bed of thorns and a quince stem!15

Food is the most illustrative way to express rivalry between prospective in-laws: in Los de la novia [Those of the bride], the groom's family complains that the bride's family eats cream, while they have to bear curses. In La madre de esta novia dice que la perdonis, the bride's mother begs forgiveness for not preparing a good enough meal and promises to make up for it in the future; in one version of the song, it's obvious that she has no intention of ever doing so!

Betrothal and wedding songs shed a little light about eating customs and celebratory foods. In some communities, the bride would be fattened up for her wedding, as we hear in the song Mira novia [Behold bride], from Istanbul: "She has fattened to two and a half times her size."16 This custom is borne out by postcards showing obese brides from Tunisia. 17 The popular dance song Ay que buena / Yo le mandi [Oh, how blessed / I sent him] describes the exchange of gifts between prospective bride and groom: he sends her silk and laces, while she bakes him borequitos (or pastelicos). We also learn about sending cakes as betrothal gifts in the Purim (Shabbat "Zakhor") song above.

A song about a broken engagement - Mama yo no tengo visto [Mother I cannot see] refers to the practice of sending sugared almonds to invitees. A spirited wedding dance, Viva Ordueña, takes us through the whole process of making bread, from sowing of the seed to eating the bread.

Drink

Ande entra el bever sale el saver. [Where drink comes in, good sense goes out].

The most well-known drinking song in Ladino is La vida do por el raki [I give my life for raki] - (lyrics) - a song of maudlin self-pity set to a rolicking tune. Just how popular raki (the equivalent of Greek ouzo) is in Sephardic society is described in this fascinating article.18 A more upbeat message about wine and women is expressed in Mi vino tan querido [My cherished wine] (see the video, beginning at 2:30).

Wine is an integral part of Jewish life.19 It is an essential component of a well-stocked home (for example, the bride's song, Desde hoy la mi madre [From today on, my mother]) and it accompanies good meals, as can be seen in the berendjena [eggplant] song above. It flows freely in life-cycle events and festivals, particularly during the festival of Purim: see the complas de Purim (above).

Wine can also be abused, as we hear in the song Mi querido bevió vino [My love drank wine], which tells of the near-murderous consequences of drunkenness.

Food - A reflection of values

Como lo guizes, lo comerás. [The way you cook it is the way you'll eat it.]

The Jewish housewife [ama de casa] is virtually synonymous with good cooking. A girl who wasn't able to learn how to cook was roundly censured: Una muchacha en Selanica / Zimbolucha [Hyacinth] tells about a young girl in Salonica who, when her mother hit her for burning yapraquitos [stuffed grape leaves], converted to Islam. This way she could escape her mother's authority, but, as the song says: "She was as Jewish as anyone can be, but now she has became a Turk, and all because of stuffed grape leaves: was it worth it?" (By the way, the housewife in the Yiddish song Hot a yid a vaybele [A Jew has a wife] is threatened with divorce for burning the Shabes kugel. tongue-in-cheek or serious as these songs may be, the implicit values are nevertheless clear).

Food also has (inverse) snob value. As Turkish government and people became more westernized from the beginning of the 20th century, the Jewish population, too, wished to follow European [a-la-franka] fashion. Songs poke fun at aspiring parvenus such as Madmuasel Sarika, who wants to ride out in a carriage, and Maurice, who promenades wearing his hat, tie and walking stick (Pamparapam) - they are advised to eat simple kashkaval cheese! Ruku also dreams of living beyond her means. She wants a European bed with white cotton pillows and she wants to eat one and a half portions of bread - what's wrong with eggs?

Love

Más vale pan con amor que gallinas con dolor. [Bread with love is worth more than chickens with sadness.]

We all know that the way to a man's heart is through his stomach, but metaphors in Ladino love songs tend towards flowers rather than edible delicacies! Nevertheless, there are a few songs featuring food which throw some light on romance in Sephardic culture. In the song La comida la mañana [The morning meal], a young lass too lovesick to eat her breakfast is cautioned by her mother: "In our days", says the mother, "we did it with love. But the young women of today are forsaken and left to grieve."

The consequences of disappointed love can be dire indeed! A rarely-heard romansa [narrative ballad], La envenenadora [The poisoner], relates the story of a young woman who poisons her lover at their evening meal! When he awakens, groaning with pain, she relents, offering him chicken soup,20 roasted pigeons and money - but it is too late!21

What's true love? Mansevo dobro [An honest young man] suggests to his love that they escape their family troubles and go to Palestine: "I can support you ... and you'll fry fish for me with beets and garlic sauce ..." [Sigh ...!]

Proof that food is the music of love comes from the song Las compras del rabino [The rabbi's purchases] / Ya se va el rabino: The rabbi goes out to buy gifts for his wife: an embroidered blouse, pita and halvah, and a gold bracelet. She has brought him mazal [good luck] and good fortune.

Fruit and vegetables

A la pera dura, el tiempo la madura. [Time will ripen a hard pear.]

Fruit and fruit trees carry significant weight in Sephardic culture, and are often referred to in Ladino songs. (It's no wonder that lemons illustrate Claudia Roden's "New Book of Middle Eastern Food" - see the collage above). Songs which praise God, creator of flowers and fruit, are sung on the festival of "Tu Bish'vat" [15th Sh'vat: Jewish Arbor Day]. One of these is Complas para noches de frutas [Song for the night of the fruit], similar in nature to the copla El debate de las flores [The debate of the flowers] and the piyut Az yeranen [Then it will sing].

In Sephardic (Spanish) culture, fruit may symbolize beauty and fragrance. Almond trees, with their beautiful blossoms and delicious nuts, are an essential feature of the landscape and diet; we learn this, for example, in the love song Arvolicos d'almendra. In the song Una matica de ruda [A branch of rue], a girl of marriageable age argues aginst her mother's good but stolid sense - "Better a wretched husband than a young lover"; the daughter answers that a young lover is like apples and fresh lemon. However, the apple may be "rotten to the core": Mansanica corelada [Red apple] is the image referred to in a song from Sarajevo bemoaning unattainable love.

Fruit trees in wedding songs symbolize virility, fertility and prosperity. Verses of the popular wedding song Morenica [Dark maiden] illustrate the bountifulness of fruit: Morenica is dressed in green and pink-purple, like the colours of the pear and the peach; now she is dressed in shades of saffron, like the pear with the quince. In the mikveh [ritual bath] song Ya salyo de la mar la galana, the lovely maiden comes up from the sea to behold a landscape of cinnamon, almond and quince trees.

The fruit and vegetable garden is also a symbol of fertility: once esconced in her new home, a young bride is proud of the apples, pumpkins and quinces she has produced, to the chagrin of her inlaws: En la mi guerta vey mama [In my garden, see, Mother].

Which food is best?

Alábate coles que hay nabos en la olla. [The cabbage should praise itself because there is turnip in the pot].

In "Debate de los comidas"/ "Debate de los comestibles" [Debate of the foods] - a copla based upon "The debate of the flowers" (the Tu Bish'vat song of praise discussed above) - various foods vie for the honour of praising God.22 Depending upon the song variants, the foods competing against each other include the olive, watermelon, fish, liquor (raki / arak), chicken, egg, or cherry. For example, the chicken claims that it is the food of kings, whereas raki boasts that it is served to sadikim [righteous people]. (The foods in these songs are typically Mediterranean: for a comparison between Sephardic and Ashkenazic food, see below!)

Children's songs

La masa y el niño en el verano tienen frío. [Both dough and a child are cold in summer.]

A few children's songs feature food: one is the very popular Chi chi bunichi, a finger-counting nursery rhyme from Sarajevo: "This one asks for bread, this one asks for cheese ... The hen lays an egg - here, here, here - into the mouth of my little child."

Another popular children's song from the Balkans is Si veriash a la rana [If you could see the frog] ... and other animals doing impossible things with food: the frog frying fritas, the mouse shelling walnuts, and the camel rolling out phyllo pastry.

We began this webpage with a song by Flory Jagoda, so let's end with one of her children's songs - Chiko Ianiko: Little Ian, little birdie, he's making burekas for us with cheese and butter.23 "Oh, what fun to bake with Nona," says Grandma Flory in the disk notes. "I remember the delicate pastry dough the Sephardic women took such pride in making. When the grandchildren 'helped', the flour was everywhere and the kitchen was a mess ... but, oh, we had such fun!"

Fritas and Phyllo pastry

Conclusion - and a puzzle

Revuelta de mares, ganancia de pescadores. [If there's a storm at sea, the fishermen benefit.]

To conclude, perhaps you can help me make sense of the opening scene of La serena [The siren / Serenity] - one of the most popular songs in the Ladino repertoire - beginning with the words "Si la mar era de leche" [If the sea were made of milk]. What does "milk" refer to? Is this an image of a man fishing precariously in a sea white with foaming waves? Or, on the contrary, is this a picture of calm serenity, the sea white and still? Is it, perhaps, a sexual allusion, with milk symbolizing femininity and cinnamon virility? Surely the gastronomic images aren't meant to be taken literally - or are they?

En la mar hay una torre, en la torre una ventana ... [In the sea there was a tower, and in the tower was a window ... ]

And now it's time to stop reading and start eating. If you like, here is a brief beraha [blessing] in Ladino to be said over the food (scroll down to June 19, 2012). Al gusto! - Bon appetit!

* * * * *

Notes

1 What's better: Ashkenazi or Sephardic food? One would think that this is a matter of culture and taste, but at a "Gefiltefest" at the London Jewish Cultural Centre (2013), Ashkenazi and Sephardic cooks were pitted against each other to see who could make the best potato and egg dish. Guess who won?!

2 Raphael, Sh. A song of praises regarding the eggplant. Ladinar, vol.3, 2004 [in Hebrew]

ש. רפאל, שיר תהילות החציל, לאדינאר ג (תשס"ד), עמ' 84-65.

3 How to prepare eggplants:

- Counting the ways to cook an eggplant.

- 15+ tasty ways to prepare eggplant.

- How to keep your aubergines from exploding + Claudia Roden's eggplant dips

4 Saltiel, A. & Horowitz, J. The Sephardic Songbook. Frankfurt, Peters, 2001.

5 This copla is also called El testamento de Aman [Haman's will].

6 Dobrinsky, H.C. A Treasury of Sephardic Laws and Customs. Yeshiva University Press, 1986. C.21 - "Purim".

7 Garfinkle, Bouena Sarfatty. Adar and Purim in Salonika.

8 Sephardic Hanukkah cooking:

- A Sephardic Chanukah.

- Sephardic Jews' Hanukkah treats have a rich history, too.

9 Benvenisti, David. The Jews of Saloniki. Kiriat Sefer, 1933. [In Hebrew]

10 Ladino songs celebrating Shabbat belong mostly to the gender of coplas, songs generally sung by men which are associated with the Hebrew genre of piyutim: an example is La creacion del mondo [Creation of the world], a Ladino equivalent of the piyut Erets verum [ארץ ורום - Earth and heaven].

11 "A Different Night: A Passover Musical Anthology" - Disc by Voice of the Turtle. The song actually begins with the third night.

12 See the related paragraph on folk-songs related to Chad Gadya.

13 Cohen, J. (1987). The lighter side of Judeo-Spanish traditional song: Some Canadian examples. Canadian Journal for Traditional Music.

14 Pedrosa, J.M. Canciones. In Hemsi, Alberto. Cancionero sefardi (ed. by E. Seroussi, in collaboration with P. Diaz-Mas, J.M. Pedrosa & E. Romero). Jerusalem: The Jewish Music Research Center.

15 Weich-Shahak, S. (1980) Judeo-Spanish Moroccan Songs for the Life Cycle. Jerusalem: The Jewish Music Research Center.

16 Boda - Sephardic Wedding Songs. Disk by Ensemble Saltiel.

17 Salamon, H. & Juhasz, E. (2011). "Goddesses of flesh and metal": Gazes on the tradition of fattening Jewish brides in Tunisia. Journal of Middle East Women's Studies, Vol.7, no.1.

18 Normand, E. & Maimon, A.S. (2015). The Sephardic drinking song, "I give my life for a taste of raki". Sepharic Horizons, Vol.5, Issues 1-2.

19 Koen-Sarano, M. El vino en el kuento, el kante i el reflan djudeo-espanyoles. [Wine in Judeo-Spanish stories, songs and proverbs]. Ladino: Lengua y Cultura.

20 Apparently the "Yiddishe mame" does not hold exclusive rights to chicken soup as a cure-all!

21 On the surface, the lover of this romansa suffers the same fate as the more famous victim of poisoning, Lord Randall; however, I believe that the story and style (especially the opening) have more in common with the night-visiting genre. For different victims of poisoning, see the "cruel mother-in-law" songs.

22 Susana Weich-Shahak describes a whole genre of disputes based upon the "Debate of the Flowers" in her article (in Spanish) "Debatos coplísticos judeo-españoles".

23 The kashrut authorities in Israel may soon vie with traditional Sephardic housewives over the shape of borekas, viz Rabbinate regulates burekas shapes!

Recommended viewing and reading (including recipe blogs)

Gizando i kantando [Cooking and singing]: A fascinating series of videos, taking the viewer into the houses of Sephardic homes for delicious home-made recipes accompanied by song

Ashkenazi Jews embrace Sephardic fare. My Jewish Learning.

Bendichas manos (Bendichos manos)

The Boreka Diary

Cuisine of the Sephardic Jews. Wikipedia.

Guttman, Vered. Ladino in the air, Sephardi foods on the table. Washington Post, September, 2012.

Koén-Sarano, Matilda. La komponente kulinaria i linguistika turka en la kuzina djudeo-espanyola.

Roden, Claudia.

- A Book of Middle Eastern Food. Penguin Books, 1968.

- The Book of Jewish Food: An Odyssey from Samarkand to New York. Knopf, 1997.

- The New Book of Middle Eastern Food. Knopf, 2000.

- Arabesque: Sumptious Food from Morocco, Turkey and Lebanon. Michael Joseph, 2005.

Sephardic Food. Janet Amateau's blog.

Sephardic Food project

Tapuz blog on Sephardic recipes (in Hebrew)