Jewish Weddings

Naciemiento, casamiento y mortaja, del cielo baja [Birth, wedding and shrouds come down from heaven]

Oyf ale kales shaynen di brokhe fun di shkhine. [The blessing of the Divine Presence shines upon all brides]

"My Big Fat Greek Wedding" has become a catchphrase for ethnically traditional weddings hovering on the brink between preservation of traditional values and surrender to the pressures of assimilation. The word "Greek" can easily be - and often is - substituted by other cultural references (Italian, Gypsy, Indian), as well as "Jewish". There is no question that Jewish weddings are facing similar cultural pressures to those depicted in the film, and also that weddings held today are very different from those of a century ago. One of the ways we can learn about weddings in the past is by studying the songs which have been handed down. On this webpage, I shall be asking what we can learn about traditional Sephardic and Ashkenazi weddings from Ladino and Yiddish folksongs. (If anybody reading this would like to contribute a section to weddings of other Jewish cultures, I'd be more than happy). The page is divided into three main sections:

1) a brief summary of the Jewish marriage ceremony; 2) Sephardic songs and traditions; and 3) Ashkenazi songs and traditions. (More specific information on "in-laws" may be found here).

The Jewish Wedding Ceremony

Jewish marriages have traditionally begun with the services of a matchmaker (shadkhn / el casamentero). God created the first couple and, according to the Talmud, has been occupied in shiddukhin [creating matches] ever since.

The Jewish wedding ceremony is held under a "chuppah", which is either a canopy, held aloft by four poles over the whole bridal party, or a tallit [prayer shawl] covering the bride and groom. The ceremony consists of two parts, erusin [betrothal] and nisu'in [nuptials], which were originally up to a year apart but have been held consecutively since the Middle Ages. In the first stage, the groom gives the bride a ring, thereby declaring his intention to marry her. This stage is also called kiddushin [consecration]: the blessing "Harei at mekudeshet li" [You are hereby consecrated to me] implies that the bride is now "set apart" for the groom, and that their union, although not as yet consummated, can only be dissolved by divorce. In the second part of the ceremony, nisu'in, the couple's married status is affirmed, their union culminating in yichud ["seclusion" / "togetherness"] which, for Ashkenazi Jews, means being alone for the first time immediately after the wedding ceremony or, for Sephardic Jews, going home together after the wedding banquet. Sheva berachot [seven wedding blessings] are recited over the new couple, often by honoured guests. The seven blessings are also repeated for seven nights following the wedding ceremony, beginning on the night of the banquet itself. Betrothal and marriage are separated by reading of the ketubah [marriage contract]. (The content and significance of the ketubah is different for Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews. Ashkenazi Jews may also hold a separate pre-wedding ceremony - called the Vort - in which the tena'im [conditions] are signed). The wedding ceremony ends with the groom stepping on a glass, in remembrance of the destruction of Jerusalem (see video: "If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning").

Here is Jo Amar1 singing the seventh blessing in Sephardic tradition:

It's customary for the wedding guests to join in the singing of the last blessing, "Asher bara" [Who created]: “You are blessed, Lord our God, the sovereign of the world, who created joy and celebration, bridegroom and bride, rejoicing, jubilation, pleasure and delight, love and brotherhood, peace and friendship. May there soon be heard, Lord our God, in the cities of Judea and in the streets of Jerusalem, the sound of joy and the sound of celebration, the voice of a bridegroom and the voice of a bride, the happy shouting of bridegrooms from their weddings and of young men from their feasts of song. You are blessed, Lord, who makes the bridegroom and the bride rejoice together.” Here's a traditional melody by Carlebach and a new Modhitz composition. Verses from "Song of Songs" are also often sung at the chuppah.

Moritz Oppenheim - Die Trauung [The Wedding], 1861 (detail of the full painting)

Notice the following: The bride and groom are covered with a cloth veil - tallith? (not a canopy); the bride is standing to the left of the groom; she is extending the first finger of her right hand; the rabbi is holding a bottle (not a cup) because virgins drank from a "closed, narrow-mouthed jar". (Sperber, C.21)

The elements of the wedding ceremony summarized above are central to most Jewish communities. (Egalitarian Jews today retain the elements of covering, blessing, commitment and remembering, but seek to find an alternative to the principle of kiddushin). However, there is a wealth of different customs associated with ethnic and national traditions, as expressed in food, dress, proverbs and music, beginning from the first stages of matchmaking and engagement through to the commencement of "real life" a week after the ceremony. In the next two sections, I'll discuss how Ladino and Yiddish folksongs reflect respective marriage customs.

* * * * *

Sephardic songs and traditions

Qien canta, su mal espanta [Whoever sings sends bad feelings away]

There is an extensive body of traditional Sephardic wedding songs accompanying the multiple stages of wedding preparations and ceremonies. These were mostly sung by groups of women, who punctuated the singing with ululations and accompanied themselves on the tambourine [sonaza or panderika]. When the men met, they would mainly sing piyutim [Hebrew liturgical poems].2 (In this review, I shall be talking about Sephardic customs in general, but it's important to bear in mind that there were significant regional variations, especially between the east and west).

Traditionally, bride and groom were very young. Chances are that the bride and groom knew each other, as marriage within the extended family or the immediate neighbourhood was favoured. (In the song Oy que buena [Oh, how good], the girl has fallen in love with her first cousin). A meeting-place for young people to view each other and express their opinions in song was the neighbourhood swing [la mateša]. After a match was approved by the parents, negotiations between the two sides began. The young man would send his fiancée an engagement ring [anillo de kedushin] and silk for a dress. In return, she would send her groom embroidered handkerchiefs, pastries and sweets (as described in the song Yo le mandi a mi novia [I sent it to my bride]).

The engagement could last up to a year, during which the bride's trousseau [el ajuar / ajugar / ashugar] was readied, a process which had commenced at birth (Ashugar de novia galena [The trousseau of the lovely bride]). One of the things that the bride had to provide was the bed, including the mattress. On the day on which the wool for the mattress was bought and washed [el dia del lavado de lano], relatives, girlfriends and neighbors who came to help clean and bleach the wool sang Lavaba la blanca nina [The pale girl washed], a variant of the romansa telling about the husband's return [La vuelta del marido].

A few days before the wedding, two preciadores [appraisers] came to the bride's house to evaluate her trousseau. The dowry was an extremely important indication of social status, and a large dowry could allow the bride's family to aim for a talmid chacham [Jewish scholar] or for a groom from a respected family.3 Too little could occasion disapproval on the part of the inlaws, as reflected in the groom's mother's song Poco le das, la mi consuegra [You're giving too little, my inlaw].

The Shabbat before the wedding was called El Saftarray (or Almosana). The bride's friends came to her place to sing, dance and feast, and the groom also held a "bachelor party" for his friends. From now till the wedding, the bride and groom would not see each other.

The next major occasion was El baño de novia [the bride's bath]. Formerly, the groom had given his fiancee a package of bathroom accessories for her upcoming visit to the mikveh [ritual bath]. She, in return, had given him a bogo de novio [bridegroom bundle], containing shaving accessories and other gifts.The centrality of the mikveh in the Sephardic woman's life is reflected in the large number of baño songs. A particularly popular one is Ya salio de la mar, la galana [The young beauty came out of the sea], where the bride awaits her mother-in-law's permission before jumping into the sea.4 The baño repertoire includes songs praising the bride's beauty, such as the cumulative Dize la muestra novia [Our bride speaks].

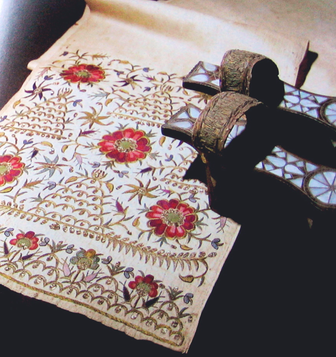

Embroidered towels and inlaid clogs for the mikveh, Rhodes

Similarly to brides living in other oriental environments, Sephardic women also practiced the ritual of painting hands (and feet) with henna 5, either at the baño or on the night before the wedding, La noce de la novia. On the eve of her wedding, the Moroccan bride would wear a traje de berberisca, an elaborate eight-piece costume encoded with Jewish symbols, and sit on her throne. This is described metaphorically in the song Scalerica de oro, which depicts a groom climbing up a ladder of gold to grant kiddushin to his bride. This song also refers to the practice of giving financial help to a poor bride. A corresponding song in the Moroccan Haketia dialect is De veinticinco escalones de oro fino [25 steps of fine gold].

Traje de berberisca

Finally, the day of the wedding arrived. A special service was held in the synagogue for the groom and his family, at which he vowed to uphold the stipulations in the ketubah (marriage contract) which had been drawn up in the preceding week. The bride, who had been accompanied in procession from her house to that of the groom the night before, had already arrived at the reception and was seated between the two mothers.The wedding blessings for erusin and nisu'in were recited to the couple standing underneath a tallith. (Note that, unlike the Ashkenazi ceremony, the Sephardic couple does not fast and does not observe the custom of yichud).

Wedding songs were sung during the bridal processions to the mikveh and the groom's house and at the banquet festivities. Perhaps the most well-known of all is Morenica [Little dark girl] - Shecharchoret in Hebrew.6

Another popular song which celebrates the beauty of the new bride is Arrelumbre, arrelumbre [Shine, shine]: the bride shines like gold and enamel. Beauty is not only skin deep: the importance of moral integrity is implied in Esta Rahel lastimosa, a romansa - one of the few in the wedding repertoire - praising the steadfastness of a married woman. (The heroine of the original romansa was actually convicted of adultery, but in the Jewish version she remains loyal to her husband). Many of the songs are explicitly or metaphorically erotic, such as Levantisme, madre [I arose, mother]. Bayla, bayla [Dance, dance] is one of the few dance songs performed at the wedding. Two others - Viva Ordueña and El baile del cereal - are cumulative, describing the process from planting corn to making bread.

For the seven days of the sheva berachot, the newly married couple were feted royally by relatives and friends at home. They left only to go to the synagogue service on el sabado del talamo [the Shabbat of the Crown], at which the groom was called to the Torah to read Avraham siv, the portion in which Abraham sends his servant Eliezer to find a bride for Isaac. Wedding celebrations finally ended with the purchase and preparation of a fish - a symbol of fecundity7 - on El Dia del pescado [the Day of the Fish].

To conclude this section, here is a medley of some of the wedding songs sung by Jewish women of north Morocco, performed by Vanessa Paloma, Judith Cohen and Tamar Ilana.

* * * * *

Ashkenazi Songs and Traditions

Az dos vayb iz a malke, iz der man a meylekh. [When the wife is like a queen, the husband is like a king].

Ashkenazi Jews do not have a distinct body of song accompanying wedding functions as the Sephardic Jews do. For example, all Jewish brides are required to go to the mikveh, but, in contrast to Sephardic brides, Ashkenazis go quietly, accompanied only by their mother and perhaps another friend or two. Another example is the bridal procession, which was likely to have been accompanied by instrumentalists but not by singers, as may be seen in the paintings below.

Trankowsky, A. - Jewish Wedding (late 19th century)

Chagall, M. - Russian Wedding (1909)

The Yiddish wedding repertoire includes folksongs on marriage-related topics - such as finding a suitable husband, participating in the wedding banquet, parting from parents, or dealing with inlaws - but these were sung by individuals in an intimate setting rather than by groups of women. Examples of such folksongs are: Vos zhe vilstu? [What do you want?] - a dialogue between mother and daughter; Bayt zhe mir a finf-un-tsvantsiker [Change me a twenty] - inviting the musicians at the wedding to play; Mekhuteyneste mayne [My inlaw] - inlaw rivalry; or Di goldene pave [The golden peacock] - the unhappy bride. Here is an absolutely wonderful rendering of the folksong Di khasene [The wedding] - a humorous description of a wedding and its participants - which the singer, Leibu Levin z"l, says that he learnt from his mother.

In the twentieth century, folk bards such as Warshavsky and Gebirtig wrote popular songs about weddings and marriage - such as Di mezinke oysgegebn [I've given away my last daughter] or Dray tekhterlekh [Three daughters] (see videos below) - which very quickly passed into the realm of folklore. During the flowering of Yiddish culture in the USSR before the Stalinist purges, songs written about weddings included A yidishe khasene [A Jewish wedding] by Feffer and Yampolsky. Another source of songs was the Yiddish theatre in America, e.g., Rumshinsky's Di goldene kale [The golden bride] or A khasene in shtetl [A village wedding] by William Sigal.

Dray tekhterlekh and A yidishe khasene

The Ashkenazi wedding was very different from its Sephardic counterpart in a number of significant ways. The young couple fasted on the day of the wedding, which was regarded as a Yom Kippur [Day of Atonement], in order to achieve a state of purity and atonement.8 The wedding ceremonies began with the groom seated at his "table" [khosns tish] together with his father, father-in-law and friends, and the bride seated on her "throne" [kale bazetsn], attended to by the women. At the khosns tish, the groom would sign the ketubah in the presence of two witnesses. He would also begin to deliver a derasha [speech], which would inevitably be interrupted by friends; on his third attempt, he would be lead, singing and dancing, to his bride for the badekn [veiling] ceremony, the purpose of which was to ascertain her identity (in contrast to what happened to the patriarch Jacob) and also to enact the modesty displayed by the matriarch Rebecca when she first saw Isaac. Bride and groom would be able to spend a few moments together and break their fast in yichud [seclusion room]. In general, lively music would be chosen for this part of the ceremony, as can be heard in the Bedeken video below; in Chabad weddings, however, the solemn Alter Rebbe's nign would be played.

As the couple left the yichud room to join their guests, they would be greeted by a long round of lebedik [lively] dances - beginning, usually, with Khosn kale mazl tov! - and then participate in the se'udat mitsvah [wedding feast].

All the different ceremonies of the wedding celebration were coordinated by the badkhn [jester].9 At the kale bazetsn, his role was to warn the bride of the seriousness of married life (just as we hear in Warshavsky's Kalenyu, veyn zhe, veyn! [Cry, my bride!]). At the khosns tish, he delivered the same message, although more eruditely. He was a master improvisor: when inviting honoured guests and family to participate in the mitsve tants [the dance honoring the bride and groom], he would weave family history (including scandal!) together with quotations from the Bible and Talmud. We can hear examples of kale bazingns and khosn bazingns [singing to the bride and groom] on the disk "Wedding without a Bride" (here is another example), and of authentic badkhones on the disk "The Hasidic Niggun as Sung by the Hasidim".

Badkhn performing before the bride - Anonymous, Poland, 20th century

All the music for the Ashkenazi wedding was provided by the band of klezmers [from the Hebrew words meaning musical instruments]. These were professional musicians playing the violin, tsimbl (cymbalom) and base, with later additions of the clarinet and other wind instruments, who played dance music in a style stemming from eastern Europe and incorporating elements of liturgical, eastern and gypsy music.10

The folksong Khatzkele [Ezekiel] enumerates some of the many dances that were played at Jewish weddings: other dances included the freylekhs [happy dance], the patsh [clapping and stamping dance], the solo flesh [bottle] dance, and the sher [scissors dance], similar to the American quadrille. (An example of a song set to a sher melody is "Hot zikh mir di zip tzezipt", sung here by Ruth Rubin).

The Barry Sisters, singing "Der Nayer Sher", by Abraham Ellstein

The broygez [angry] dance, a pantomime-like performance in which the mothers-in-law pretended to be angry with each other, was followed by the sholem [peace] dance, which occasioned two of the few songs sung at the wedding: Lomir zikh iberbetn and Bistu bay mir brogez. (Read a detailed description of the broygez tants in Feldman, below). Sometimes the broygez tants was substituted by the tekhiyas hamesim [resurrection of the dead] dance, which could symbolize any type of quarrel and peace-making.

Another family dance was the krenzel [crown] or broom dance, performed towards the end of the wedding of the youngest daughter (Di mezinke oysgegebn, by Warshavsky).11

The Admor of Pinsk-Karlin dancing the "Mezinke" at his youngest daughter's wedding

A modern version of the Mezinke

"Keitzad merakdim?" How do we dance before the bride?" argue the Houses of Hillel and Shammai in the Talmud. The author of the Kitzur Shulhan Arukh [the Condensed Code of Jewish Law] answers that "It is a mitzvah to gladden a groom and bride, and to dance before the bride, and to declare that she is attractive and performs acts of lovingkindness, and indeed we find that [the talmudic sage] R. Ilai would dance before the bride." Today, too, the highlight of any traditional wedding is the mitzvah dance, in which honoured guests and family dance for the bride and groom.

Here is a photo-essay of a contemporary ultra- orthodox wedding, in which the young couple carry on traditions which have been followed for hundreds of years. We can also get an idea of what Ashkenazi weddings looked and sounded like from old films. "Yidl mitn fidl", the last Yiddish film produced in Poland before WWII, contains an extensive shtetl wedding sequence. Another film including wedding dances was the 1937 film "The Dybbuk".

Of course, there's nothing like wine to liven the spirits (!) There's no lack of songs about drinking in Yiddish, and there was never any lack of wine or spirits at a Jewish wedding! Here, to end this review of Jewish weddings, is a version of the tekhias hameytim [revival of the dead] dance demonstrating the dangers of drunkenness!

* * * * *

Notes

1 Notice Shlomo Carlebach in the background. At the same wedding, he sang Lecha Dodi [Come, my beloved], a piyut about Shabbat the bride and the heavenly union between the Shechinah [God's presence] and the Jewish people. This mystical concept is also expressed in the Separdic synagogue service on Shavuot, when "Ketubah le-Shavuot" is recited. A copla entitled "La Ketuba de la Ley" [The marriage contract of the Law] expresses this same idea.

2 Two piyutim sung in honour of groom at the synagogue were Chatan na'im aleh [Go up, pleasant groom] and Lech leshalom limkomecha [Go to your place in peace].

3 Just how significant the dowry was can be seen in the article by Hadar.

4 See the very interesting article in Hebrew by Michal Held (מיכל הלד).

5 "Eshkol HaKofer" is a very informative research blog about the Jewish henna ceremony.

6 In this video from Weich-Shahak's collecion, three informants are teaching Orit Perlman the song Morenica. (See an extensive discussion of this song here). Note how one of the ladies uses cutlery as an improvised percussionary instrument. It's very interesting to see how the melody and rhythm of the older Ladino song is unconsciously being accommodated to that of the well-known Hebrew song (Shecharchoret).

7 Symbols of fertility among Ashkenazi Jews are rice and roosters. The latter may be seen in many of Chagall's paintings.

8 There are actually many different reasons for fasting, including both atonement and mourning. (Sperber, C.20)

11 Here are two articles which discuss the origin of the "mezinke dance": (a) "Mezinke Madness"; (b) "Mezinke Oysgegayben".

References

Videos

Spielberg Film and Video Archive: Munkacs, Czechoslovakia, 1933: Scenes of Jewish life, including the wedding of the chief rabbi's daughter

Disks

Wedding songs are included in many Ladino and Yiddish disks, too numerous to list. Here are two which are exclusively devoted to respective Jewish weddings, and which contain a lot of information:

Boda, by Ensemble Saltiel (Sephardic) [links to two videos about this disk]

Wedding without a Bride, by Budowitz (Ashkenazi)

Websites

Accounts of weddings in Yizkor books

Jewish Marriage. Chabad Wedding Handbook *

Liturgy, Ritural and Customs of Jewish Weddings. My Jewish Learning

Marriage. Jewish Virtual Library

Marriage Ceremonies. Jewish Encyclopedia. (Article by C. Adler & M. Grunwald, M.)

The Jewish Wedding Ceremony. Ohr Somayach. (Article by Rabbi M. Becher) *

The Sephardic Wedding: Different than what you may be used to. (Article by Rabbi J. D. Sandberg)

Weddings. The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. (Article by Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett)*

* These sites refer mainly to Ashkenazi weddings.

Articles on the web

Baumgarten, J. (2000). Yiddish oral traditions of the batkhonim and multilingualism in Hasidic communities. Bulletin du Centre de Recherche Francais a Jerusalem.

Cohen, J. (1987). "Ya salió de la mar": Judeo-Spanish wedding songs among Moroccan Jews in Canada. In Koskoff, E. (Ed.). Women and Music in Cross-Cultural Perspective. Illini Books.

Hadar, G. (2002). Marriage as a survival strategy prior to deportations to extermination camps - Salonika, 1943. University of Haifa. Program in Modern Hellenic Studies. "The Holocaust in Greece" International Conference

Feldman, Walter Zev. (2017). Klezmer: Music, History and Memory. OUP. C.5: The Jewish wedding and its musical repertoire.

Feldman, Walter Zev. Dance. Traditional dance. YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe.

Kahan-Newman, Z. (1999). Women's badkhones: The Satmar poem sung to a bride. International Journal of the Sociology of Language. Vol.138, no.1.

Krasny, Ariela - מנהגי חתונה בעין היצירה – פתגמים ושירי עם ביידיש

הלד, מיכל. בין הנהר לים - ניתוח תרבותי ספרותי רב רובדי של שיר חתונה יהודי-ספרדי מהאי רודוס

Books and articles cited

Beregovski, M. (2000). Old Jewish Folk Music. Edited and translated by Mark Slobin. Syracuse University Press.

Dobrinsky, H. (1986). A Treasury of Sephardic Laws and Customs. New York: Yeshiva University Press. C.3: "Engagement and Marriage"

Kaplan, A. (1983). Made in Heaven: A Jewish Wedding Guide. Jerusalem: Moznaim.

Marcus, I. (2004). The Jewish Life Cycle: Rites of Passage from Biblical to Modern Times. Seattle: University of Washington Press. C.3: "Engagement, Betrothal, Marriage".

Sperber, D. (2008). The Jewish Life Cycle: Custom, Lore and Iconography. Bar-Ilan University Press. C16-28.

Weich-Shahak, S. (1989). Judeo-Spanish Moroccan songs for the Life Cycle. Jerusalem: The Jewish Music Research Centre, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Weich-Shahak, S. (2007). La Boda Sefardi: Musica, Texto y Contexto. Madrid: Editorial Alpuerto

.jpg)